Coke and Pepsi Expand

Last month, Muhtar Kent, Chairman and CEO of The Coca-Cola Company, inaugurated the opening of its 42nd bottling plant located in Yingkou, Liaoning, the largest Coca-Cola production facility in China. The new plant represents a US $160 million (1 billion in Chinese renminbi) investment in China, a small part of a three-year, US $4 billion investment plan announced last year. “China is a vast growth market for Coca-Cola. As we work to double the size of our global business in this decade, China will play a critical role,” said Kent. At its completion, the Liaoning plant is expected to reach an annual production capacity of more than 5 billion servings of sparkling and still beverages, including Coca-Cola, Sprite, Minute Maid and Ice Dew.

|

| Sprite, one of Coca Cola’s 500 branded products available in China |

Coca Cola, the world’s largest beverage company, offers its customers more than 500 sparkling and still brands including Coke, Diet Coke, Fanta, Sprite, Coca-Cola Zero, vitaminwater, Powerade, Minute Maid, Simply, Georgia and Del Valle. These beverages refresh consumers in more than 200 countries who drink more than 1.7 billion servings of its products a day. Coca Cola’s global beverage portfolio includes 15 brands that generate more than one billion dollars annually.

Nor is Coca Cola alone in expanding in China. In March, PepsiCo, Inc., the world’s second-largest food and beverage business (after Nestle) and the owner of 22 billion-dollar-a-year brands, announced a new partnership to create “a strategic beverage alliance” with the Tingyi (Cayman Islands) Holding Corp, one of the leading food and beverage companies in China. As part of the alliance, a Tingyi subsidiary – Tingyi-Asahi Beverages Holding Co Ltd (TAB), one of China’s leading beverage manufacturers – will become PepsiCo’s franchise bottler in China.

In 2010, PepsiCo announced plans to invest US $2.5 billion in its China business over the next few years. Later this year, Pepsi plans to open its largest research and development center in Asia and a pilot plant in Shanghai, reports China Daily. The research center will employ more than 100 scientists who will develop new food and beverage products for China and the rest of Asia.

“China will soon surpass the United States to become the largest beverage market in the world,” said PepsiCo Chairman and CEO Indra Nooyi. “As a result of this new alliance with Tingyi, PepsiCo is extremely well positioned for long-term growth in China. Tingyi is an outstanding operator with a proven track record of success. By leveraging the complementary strengths of each company, we’ll be able to significantly enhance our beverage business in China, reach millions of new consumers throughout the country, and create value for Tingyi and PepsiCo shareholders.”

|

| Pepsi for sale in a Chinese supermarket |

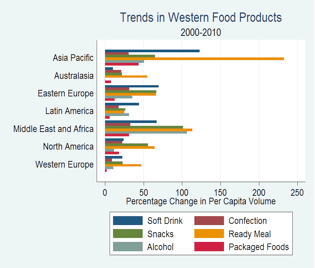

US Soda Sales Go Flat

Together, Coca Cola and PepsiCo accounted for more than one quarter of the global beverages industry in 2010, according to Datamonitor, a global business research group. In the United States, however, reports Beverage Digest, soda consumption is going flat. Throughout most of the 1990s, soda sales in the United States grew about 3 percent annually but started to slow in 1999. Since 2005, sales have been in decline as consumers concerned about health turn to options they see as healthier, such as bottled water, juice and tea. In 2011, US soda consumption fell 1 percent. According to Beverage Digest, the top four sodas — Coke, Diet Coke, Pepsi-Cola and Mountain Dew — all saw declining sales last year. Of those, Coke’s market share was flat, while the other three lost share. In part, then, Coke and Pepsi’s enthusiasm for the China market is a response to this fizzling market for sugary beverages in the United States and Europe.

To boost sales and profits, Coke and Pepsi are aggressively marketing their sugary beverages in China. Coke hired Knicks basketball superstar Jeremy Lin (actually born in Taiwan) to sell its products both in New York and overseas. In early March,reports Bloomberg News, about 100 million people in China watched the Knicks-Dallas Mavericks game on TV, offering Coke the opportunity of associating its Chinese logo with a rising sports star. “For a global marketer like Coca-Cola,” Mark O’Brien, an executive with the advertising firm DDB, told a WNYC radio reporter, “you’ve expanded your audience reach from maybe amounts that are in the millions to amounts that are in the tens to hundreds of millions.”

|

| Coke’s new salesman in China: Jeremy Lin |

In its agreement with the Chinese company Tingyi, PepsiCo will retain control of branding and marketing its drinks while Tingyi is to oversee manufacturing, sales and distribution in China. As CEO Indra Nooyi said, “The strength of both companies will help make the products available for Chinese consumers in an affordable way.” In other words, PepsiCo’s global advertising savvy will be used to seek to bring a few hundred million Chinese into the Pepsi Generation.

Health Impact of Rising Soda Sales

From one perspective, growing the market for sugary beverages in China makes perfect sense. It offers two leading American companies an opportunity to grow as sales decline in their domestic market. In theory, it offers the United States an opportunity to balance its trade deficit with China, a perennial concern for American businesses and politicians. In practice, however, Coke and Pepsi do not make the drinks they sell in China in the US and in China, they hire mostly Chinese workers. Some portion of the profits does return to the United States and this constitutes a growing share of both companies’ revenues and return on investment.

But from a health perspective, the new trade in sugary beverages constitutes a disaster. In a 2010 article in the New England Journal of Medicine, Yang and colleagues estimated that 92.4 million adults in China have diabetes with an age-standardized prevalence of diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes of 9.7 percent and of prediabetes, a precursor condition, of 15.5 percent. Moreover, like other countries around the world, China is experiencing rising rates of child obesity. In 2005, the prevalence of child obesity and overweight in big northern coastal cities in China reached 32.5 percent for boys and 17.6 per cent for girls, prevalence rates similar to many developed nations. One recent study concluded, “China is undergoing a remarkable, but undesirable, rapid transition…characterized by high rates of diet-related non-communicable diseases.”

While many factors contribute to rising rates of diabetes and obesity, increased consumption of sugar sweetened beverages (SSBs) plays an especially important role in these conditions and makes a logical target for intervention. A recent literature review by researchers at the Harvard School of Public Health concluded that “higher consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages is associated with development of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes” as well as weight gain. The authors noted that “these data provide empirical evidence that intake of SSBs should be limited to reduce obesity-related risk of chronic metabolic diseases.” To increase production and marketing of sugary beverages in a country struggling with epidemics of overweight and diabetes is like pouring gasoline on a fire.

In assessing the impact of the Opium Wars and the Treaty of Nanjing, the eminent U.S. China scholar John K. Fairbankdescribed the British opium trade as “the most long-continued and systematic international crime of modern times.” Clearly, caffeinated sugary beverages are different from opium, although a new body of research does note the similarity between “hyperpalatable foods” such as fast food and sugary beverages and the neuronal pathways activated by opioid addiction. And clearly Coke and Pepsi’s new agreements with China violate no current laws or international standards of corporate conduct.

But it is also evident that the expanded production and marketing of sugary beverages in a country caught in the throes of epidemics of obesity and diabetes dooms many, many millions of people to premature death and preventable illnesses. Soda marketing will also impose huge burdens on China’s health care system, diverting resources from other national goals such as environmental protection and improved education.

In the 1970s and 1980s, health professionals and public health advocates succeeded in dramatically reducing tobacco use in the United States and other developed nations, preventing millions of deaths. But the unintended consequences of these public health victories were to push the tobacco industry to accelerate its marketing in developing nations. In the twentieth century, 100 million people died prematurely as a result of tobacco use, but in this century it is estimated that tobacco will cause one billion premature deaths, mostly in Asia, Africa and Latin America. Now it looks like Coca Cola, Pepsi and other multinational beverage makers will follow the tobacco play book, building markets in nations that have not yet begun to turn away from sugary beverages. In the next century, will our failure to prevent this assault on health rank as “the most long-continued and systematic international crime” of our times?

Image Credit for photo 3:

Teamstickergiant via Flickr.