As part of WHO reform, the WHO Secretariat has submitted a draft framework for engagement with non-State actors, which contains: (a) an overarching framework for engagement with non-State actors, and (b) four separate WHO policies and operational procedures on engagement with nongovernmental organizations, private sector entities, philanthropic foundations and academic institutions.

Private Documents Show Coca-Cola Played Both Sides of the Drunk Driving Debate

According to the Huffington Post, at various moments over the past two decades, Coca-Cola, the massive soft-drink conglomerate, has aligned itself with Mothers Against Drunk Driving in campaigns to promote vehicular safety. But unbeknown to MADD, at the same time that Coca-Cola was helping organizations combat drunk driving, the company was also a member of a trade association that fought tougher drunk driving laws.

Most Polluted U.S. Cities

A new report from the American Lung Association lists the cities that have the worst air pollution in the U.S. In many places, such as Southern California and the Central Valley, including Los Angeles, Fresno, Visalia and Modesto, Las Vegas, and Salt Lake City, automobile and truck exhaust are primary contributors to the pollution and the health problems it causes.

New Report Documents E-Cigarette Advertising

E-cigarette makers spent $39 million on ads from June through November 2013, much of it on programming targeting youth, the anti-tobacco organization Legacy found.

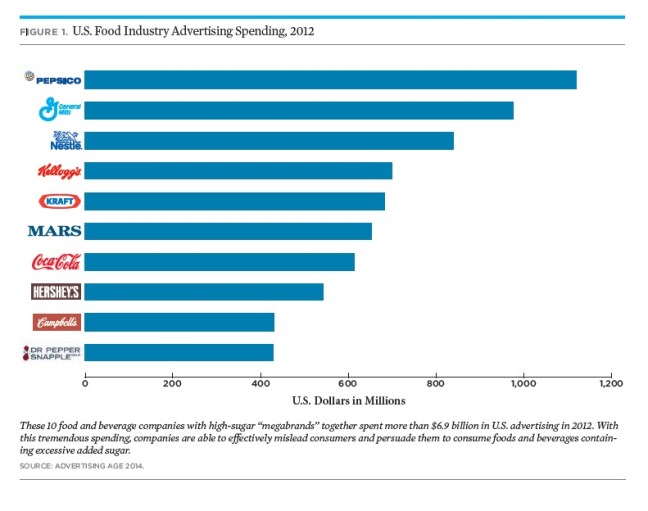

Sugar-Coating Science: How the Food Industry Misleads Consumers on Sugar

This week the Center for Science and Democracy at the Union of Concerned Scientists released a new report.

Whether or not you believe that Lucky Charms cereal is “magically delicious”, that “life tastes good” when you drink a Coke, or that “there’s lots of joy in Chips Ahoy”, the odds are good that you have heard these and others advertising slogans for sugary foods and drinks.

Billions of dollars are spent annually by food and beverage manufacturers along with industry-supported organizations such as trade associations, front groups, and public relations (PR) firms (hereafter “sugar interests”) on emotional appeals such as these. Such ads insert the brands and products into our everyday lives, infuse our psyches with manufactured cravings for them, and shape the complex relationship we have with food.

Evading Science, Engineering Opinion

While it should be no surprise to consumers that cookies and soda contain added sugar, food companies also engineer the image of many foods to appear healthier than they actually are. Many unlikely products contain surprising amounts of added sugar. These foods include breads, crackers, pasta sauces, salad dressings, yogurts, and a wide variety of other processed foods. Yogurt, for example, has nutritional benefits, and General Mills wants us to eat its brand Yoplait because it “tastes SO good” (Yoplait 2014). However, whether we choose the healthy-sounding Blackberry Harvest flavor or the more dessert-themed Boston Cream Pie, Yoplait Original yogurt contains 26 grams of sugar per serving—more than six teaspoons of sugar, which surpasses the American Heart Association’s recommendations for a woman’s total daily consumption. Yoplait Light contains 10 grams of sugar per 90-calorie serving, still a lot of sugar-laden calories for a product marketed for its healthfulness.

Scientific research shows that the overconsumption of added sugar in our diets—not just the actual calories but the sugar itself—has serious consequences for our health. Added sugars—whether from corn syrup, sugar cane, or sugar beets—are a source of harmful calories that displace calories from other, more nutritious foods, especially at the level these sugars are consumed by most Americans (O’Callaghan 2014; Hellmich 2012). As discussed in our forthcoming report Added Sugar, Subtracted Science: How Industry Obscures Science and Undermines Public Health Policy on Sugar, scientific evidence increasingly confirms a relationship between sugar consumption and a rise in the incidence of chronic metabolic diseases—obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, high triglycerides, and hypertension (Basu et al. 2013; Lustig, Schmidt, and Brindis 2012; Tappy 2012; Stanhope et al. 2011; Johnson et al. 2007; Jacobson 2005). Also, new research suggests that a higher percentage of calories from sugar is associated with an increased risk of heart disease, independent of the link between sugar and obesity (Yang et al. 2014). This scientific evidence has led several scientific and governmental bodies, including the World Health Organization, the American Heart Association, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture, to recommend sugar intake limits far below typical American consumption levels. In March 2014, the World Health Organization proposed new draft guidelines that recommend, as did the organization’s 2002 guidelines, that sugar should not exceed 10 percent of a person’s total energy intake per day (which amounts to a maximum of 50 grams per day or 12 teaspoons for a 2000-calorie diet). The 2014 guidelines further suggest that a reduction of sugar to below 5 percent of the total calorie intake per day—that is, six teaspoons—would have additional benefits, especially in slowing tooth decay, which is now globally prevalent (WHO 2014). Yet despite the existence of a great deal of scientific evidence linking excessive sugar intake to a range of health problems, and despite these science-based recommendations by prominent national and international organizations, Americans have continued to consume high levels of added sugar. One factor that has kept our sugar consumption so high is the deceptive and exploitative marketing strategies of industry sugar interests. Through advertising, marketing, and Sugar-coating Science 3 PR, sugar interests influence public opinion and consumer behavior at the cost of scientific evidence.

Their tactics trigger psychological, behavioral, social, and cultural responses that distract and manipulate consumers and divert their attention away from science-based health and nutrition information. Some companies have engaged in blatantly false advertising, and major industry trade groups have financed sophisticated PR campaigns that emphasize consumer freedom but facilely overlook the influence of sugar interests in shaping consumers’ perceptions of available food choices. The industry also targets children, women, minorities, and low-income populations—strategic for the industry, but a problem for public health. Children are unable to recognize persuasive intent the way adults do, women are exploited as the primary food decision makers in most families, and minorities and low-income groups in the United States have disproportionately high obesity rates driven by sugar interests’ concern for their profits rather than for public health. Together, sugar interests’ actions interfere with how the public responds to scientific information about added sugar, distorts our understanding of our food choices, and contributes to our continued high consumption of foods with added sugar.

Full report available here.

Business Gears Up for Assault on Consumer-Protection Laws

That low rumbling you hear, writes Bloomberg Businessweek is the business lobby revving its engines for an assault on state consumer-protection laws. The corporate-funded American Tort Reform Association gave fair warning at an event in Washington last week, when it announced “a multiyear, multistate campaign to reform such laws.” By “reform,” ATRA means water down, roll back—choose your metaphor.

Origins of Personal Responsibility Rhetoric in News Coverage of the Tobacco Industry

By the mid 1980s, the personal responsibility frame dominated the tobacco industry’s public arguments. In a new article in the American Journal of Public Health, Pamela Mejia and colleagues analyze news coverage of the tobacco industry from 1966 to 1991. They conclude that the tobacco industry’s use of personal responsibility rhetoric in public preceded the ascension of personal responsibility rhetoric commonly associated with the Reagan Administration in the 1980s.

Public Health Advocacy Institute Files Amicus Brief Comparing Gambling and Tobacco Industries

cross-posted by Public Health Advocacy Institute

The Public Health Advocacy Institute has filed an amicus curiae brief in an appeal pending before the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. The Plaintiff/Appellants are seeking to reverse a decision of the attorney general and get a question certified for inclusion on the 2014 ballot to repeal a law legalizing casino gambling in Massachusetts. The case is Steven P. Abdow et al., v. Attorney General, et al., No. SJC-11641.

Legalized casino gambling causes devastating effects on the public’s health, including not only the gambler but also their families, neighbors, communities and others with whom they interact. Massachusetts voters should not be denied the opportunity to be heard directly on the question of whether to invite a predatory and toxic industry to do business in the Commonwealth.

The harm caused by the tobacco industry’s products has been the archetype of a commercial threat to public health, and in considering the introduction of gambling industry casinos into Massachusetts, much can be learned from the object lesson of considering the tobacco industry as a disease vector. The predatory gambling industry shares much in common with the tobacco industry.

Some examples of the similarities are:

- Casinos employ electronic gambling machines that are designed to addict their customers in a way that is similar to how the tobacco industry formulates its cigarettes to be addictive by manipulating their nicotine levels and other ingredients.

- Mirroring the tobacco industry’s strategy of creating scientific doubt where none truly exists, the casino industry has co-opted and corrupted scholarship on the effects of gambling through the use of front groups that funnel money to beholden scientists who are able to sanitize its origin.

- Borrowing another tobacco industry technique of shaping the debate around its products, by creating a misleading lexicon and using euphemisms, the casino industry has tried to influence debate, deflect criticism and mislead the public about its role as a disease vector.

- By employing personal and corporate responsibility rhetoric honed by the tobacco industry, the casino industry hopes to gain and maintain social acceptability and stave off litigation, regulation and citizen-driven activism.

Both the tobacco and casino industries profit from preying upon society’s most vulnerable members, acting as disease vectors which adversely affect the physical, emotional and social health of the individual users and the communities where use of the products is prevalent.

The brief declares that the voters of the Commonwealth should be allowed to act on their own behalf in expressing an opinion of this type of predatory behavior. The power of the citizen ballot initiative is the ultimate in personal responsibility, agency and self-determination. Therefore, PHAI asks the court to compel the attorney general to certify the Plaintiffs’/Appellants’ petition and allow the repeal measure to be included on the 2014 ballot.

The full brief can be downloaded here.

Court-Ordered Tobacco Ads Will Include Black Media

ABC News reports that the nation’s tobacco companies and the Justice Department are including media outlets that target more of the black community in court-ordered advertisements that say the cigarette makers lied about the dangers of smoking, according to a brief filed in U.S. District Court in Washington on Wednesday. The advertisements are part of a case the government brought in 1999 under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations.

General Mills Proposes, Then Withdraws Limits On Class Action Lawsuits

Huff Post writes that General Mills, the cereal company, last week revealed a new rule that prevented people from joining class action lawsuits if they “joined [its] online communities.” Such actions might include company contest, or liking the company on Facebook. Those who violated the rule would have been limited to arbitration or informal negotiations as a means of conflict resolution. But in a blogpost on its corporate website a few days later, General Mills said it was changing back to its old legal terms.