In an article recently posted on BMC Public Health, Andrea Fogarty and Simon Chapman of the Sydney School of Public Health in Sydney, Australia, conclude that restrictions on alcohol advertising currently have low newsworthiness as a standalone issue. Future advocacy might better define the exact nature of required restrictions, anticipate vocal opposition and address forms of advertising beyond televised sport if exposure to advertising, especially among children, is to be reduced.

Alcohol Consumption in China is Up

Thanks to rising demand and growing per capita disposable income, reports China Daily, China’s consumption of alcoholic drinks is expected to reach 84.37 billion liters in 2016. That represents an average annual compound growth rate of 5.9 percent from 2012, said Frost & Sullivan, a US-based market consultancy. Consumption of five major alcoholic drinks, including beer, white wine, rice wine, red wine and imported spirits, surged to 62.72 billion liters last year, compared with 46.52 billion liters in 2007.

Cleavages and co-operation in the alcohol industry on minimum pricing in the UK

A new report in BMC Public Health examines the differing interests of actors within alcohol industry on contemporary debates concerning the minimum pricing of alcohol in the UK, the cleavages which emerged between them on this issue and the impact of these differences on their ability to organize themselves collectively to influence the policy process.

PLoS Medicine on Manufacturing Epidemics

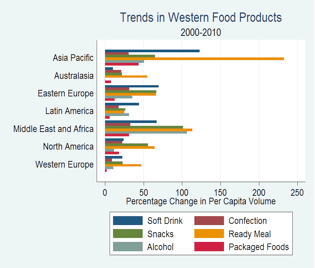

In a new report in the PLoS Medicine series on Big Food, David Stuckler, Martin McKee, Shah Ebrahim and Sanjay Basu describe the role of the alcohol, tobacco, and food and beverage industries in rising rates of consumption of unhealthy commodities, especially in low- and middle income countries. They write:

Unhealthy commodities are highly profitable because of their low production cost, long shelf-life, and high retail value. These market characteristics create perverse incentives for industries to market and sell more of these commodities. Coca-Cola’s net profit margins, for example, are about one-quarter of the retail price, making soft drink production, alongside tobacco production, among the most profitable industrial activities in the world. Indeed, transnational corporations that manufacture and market unhealthy food and beverage commodities, including Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, and Cadbury Schweppes, are among the leading vectors for the global spread of NCD risks. Increasingly, they target developing countries’ markets as a major area for expansion.

Unweighted Trends in Unhealthy Commodities, by Geographic Region,

2000-2010 and 2010-2015. Source: PLoS Medicine

Their article examines two main questions:

(1) Where is the consumption of unhealthy commodities rising most rapidly?

(2) What determines the pace and scale of these increases?

Based on analysis of market data on commodity sales in 80 countries, they offer five observations:

Observation 1. Growth of snacks, soft drinks and processed foods is fastest in LMICs (i.e. GDP≤USD12,500). Little or no growth is expected in HICs in the next 5 years.

Observation 2. The pace of increase in consumption of unhealthy commodities in several LMIC is projected to occur at a faster rate than historically in HICs.

Observation 3. Multinational companies have already entered food systems of middle-income countries to a similar degree observed in HICs.

Observation 4. Tobacco and alcohol are joint risks with unhealthy food commodities.

Observation 5. Substantial increases in consumption of unhealthy commodities are not an inevitable consequence of economic growth.

Observation 6. Foreign direct investment increases risks of rising unhealthy commodities among LMICs.

Trends in Tobacco and Alcohol Commodities, 1997-2010 and projected to 2016

Source: PLoS Medicine

The authors conclude that:

NCDs are the current and future leading causes of global ill health; unhealthy commodities, their producers, and the markets that power them, are their leading risk factors. Until health practitioners, researchers, and politicians are able to understand and identify feasible ways to address the social, economic, and political conditions that lead to the spread of unhealthy food, beverage, and tobacco commodities, progress in areas of prevention and control of NCDs will remain elusive.

For related posts on the role of the alcohol, tobacco and food industries in the production of NCDs , see here and here and here.

Rio +20: Aligning Campaigns against Global Warming and Rise of Non-Communicable Diseases

This week, 50,000 delegates will gather in Rio de Janiero for the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development. While the slogan is ambitious — “the future we want,” in comparison to the first Earth Summit held in Rio in 1992, the goals of this twentieth anniversary celebration are modest. As Andrea Correa de Lago, Brazil’s head of environment at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and chief negotiator on climate change, said last February, “It is not an idealistic conference, we are not going to say we are saving the planet through goals and measures that we know are not going to be taken seriously.”

Rather, the opportunity for this meeting is to create a framework for longer term discussion about how best to promote a sustainability agenda. One difference for this year’s conference compared to 1992 will be the active participation of city governments, NGOs, and the private sector. As a result, said Rodrigo Rosa, Rio+20 coordinator at Rio de Janeiro’s Mayor’s Office, “Rio+20’s strength will not be inside the offices, but in the movement. This year we’ll have a great amount of parallel events that didn’t happen in 1992. Politicians are reactive, they take decisions after there’s will in civil society. I think Rio+20 will contribute to that.”

For public health activists seeking to build a movement for sustainability, Rio+20 provides an opportunity to consider the causes and solutions to two of the gravest threats to global sustainability: human-induced climate change and the rise of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer and respiratory conditions. A recent report in Lancet summarizes the connections between climate change and NCDs, arguing that many of the world’s “development goals have not been achieved partly because social (including health), economic, and environmental priorities have not been addressed in an integrated manner.”

As Manish Bapna, Acting President and Executive Vice President & Managing Director of the World Resources Institute recently observed, developing effective strategies to achieve more sustainable economic growth requires addressing two related trends:

- The rise of the multinational corporations. Having grown dramatically in size, reach, and number in recent decades, global corporations wield increasing influence over the environment and society. Global supply chains only magnify their role. Today, what happens in a factory in China, South Africa, or Thailand can reverberate around the planet.

- The expansion of the global middle class. Exploding growth in the developing world has created a vast new middle class, which could near five billion by 2030, of whom 66 percent will live in Asia. That is a lot of new consumers. How will they live, eat, shop, and get to work? Will they emulate the worst habits of the developed world, or will they embrace a role as better stewards of the planet?

In fact, the rise of both NCDs and global warming in the last few decades can be explained in significant part by the efforts of multinational corporations in the automobile, energy, food and beverage, tobacco, alcohol, pharmaceutical and other industries to target these emerging middle classes in China, India, Brazil, Indonesia and elsewhere for their brand of hyper consumption. As markets become saturated in developed nations, these new markets are the corporations’ hope for profitability in this century. But the lifestyle that corporations promote to achieve their business goals is itself a fundamental cause of unsustainable energy use and chronic diseases. Its remedy requires changing not individual behavior but corporate practices. As the Third World Network, an NGO in Malaysia, put it in their Rio+20 briefing paper, “If governments want to enable sustainable development, then they must regulate transnational corporations who are drivers of unsustainable development.”

In past global meetings, much of the focus has been on what governments can and should do, an important and appropriate topic of discussion. But it is equally important to ask what corporations cannot do if sustainable growth is to be achieved. A Lancet editorial hopes that in the future, Rio+20 “is looked upon as launching a new era for human wellbeing, one that is rooted in principles of equity, social justice, and sustainability.” Achieving that goal will require a willingness to reconsider the role of multinational corporations in today’s world. Rio+ 20 will be judged on its progress in this critical task.

Local dominance of Asian Alcohol Markets Presents Growth Opportunity for Multinational Alcohol Companies

Across the globe, liquor is still a local game, at least for now. Global brands account for only 60 of the top 180 booze brands, reports Ad Age, based on the latest annual ranking of liquor brands that have sold at least 1 million 9-litre cases by Drinks International and Euromonitor International. The reason local brands still rule is that Asia accounts for roughly half of global spirits volume. And consumers in massive markets like China and India still gravitate to cheaper, locally made booze.

7-Eleven Threatens Children with Supersized Alcopop Bargains

In a new report “Alcopops Cheaper than Energy Drinks: 7-Eleven Gambles with Children’s Lives”, Alcohol Justice, an alcohol industry watchdog, reports that convenience store giant 7-Eleven cuts prices on supersized, youth-attractive alcopops so they are cheaper than non-alcoholic energy drinks. While on average, alcopops were the same price per standard alcoholic drink as beer, supersized alcopops in 16- to 24-ounce cans were cheaper per standard drink than similarly sized beer. Some supersized alcopops, such as Four Loko and Mike’s Harder Lemonade, entice youth with more alcohol for the price than even similar sized malt liquor.

Stop “Drink Responsibly” Charade, says Alcohol Justice

Market Watch reports that Alcohol Justice, the U.S. based alcohol industry watchdog, released an in-depth report debunking Big Alcohol’s cynical “Drink Responsibly” messages. “Alcohol producers and marketers are more interested in their public relations than public health,” said Sarah Mart, MPH, director of research at Alcohol Justice and co-author of the new report, How Big Alcohol Abuses “Drink Responsibly” to Market Its Products. “So it’s not surprising that they hide behind a vague, ineffective slogan that does nothing to reduce the annual catastrophe of harm caused by their products.”

Alcohol Industry Reaching for New Markets in Asia

As the European market decreases, big alcohol companies are searching for new Asian markets. Unregulated markets and big populations promise new opportunities for growth. Bloomberg Businessweek describes how Carlsberg, “the world’s fourth- biggest brewer, is seeking acquisition opportunities in Asia, including China, amid slowing growth in Europe.”

Big Alcohol‘s Global Playbook: New markets, reduced regulation and lower taxes

As the global alcohol industry becomes increasingly concentrated in a few big international companies, its practices around the world become remarkably similar. Public health professionals seeking to reduce the harm from alcohol can benefit from documenting and analyzing these trends and from studying the efficacy of differing responses. Several recent reports illustrate these convergences.

Developing New Markets

To expand, a company needs to develop new markets. In recent years, changing tastes in alcohol consumption, the global recession, and continuing competition from other multinationals as well as smaller national companies have created a fierce battle for recruiting new cohorts of drinkers.

Two attractive markets for the alcohol industry are youth drinkers, who promise to become lifetime customers, and women, who constitute the half of the world’s population that still drinks less.

Two attractive markets for the alcohol industry are youth drinkers, who promise to become lifetime customers, and women, who constitute the half of the world’s population that still drinks less.

In an article in the January issue of the American Journal of Public Health, James Mosher describes how Diageo, the world’s largest producer of distilled spirits, has used the Smirnoff brand of vodka to attract new youth drinkers. By developing alcopops, beverages that taste like soft drinks, including new fruit flavors, competing with beer makers to win over young drinkers, and engaging in active lobbying to win favorable regulatory rules for these new beverages, Diageo has seen its Smirnoff vodka sales take off.

In Canada and the United States, wine makers have targeted women, especially “Moms,” with new wine brands such as Mommy’s Time Out, MommyJuice and Girl’s Night Out. In an article in the Toronto Star last month, Ann Dowsett Johnston analyzed the growth of women-targeted alcohol advertising, examining the new wine brands, alcopops, and the various vodka drinks produced for women. In an interview with the Star, CHW Contributing Writer David Jernigan, the executive director of the Center on Alcohol Marketing and Youth at Johns Hopkins University said, “In the past 25 years, there has been tremendous pressure on females to keep up with the guys. Now the industry’s right there to help them. They’ve got their very own beverages, tailored to women. They’ve got their own individualized, feminized drinking culture. I’m not sure that this was what Gloria Steinem had in mind.”

Influencing Governments, Coopting Regulations

Another strategy Big Alcohol uses to advance its business interests is to weaken and coopt government’s regulatory apparatus to better meet its needs. National leaders in business-friendly states are often eager to help. In New Zealand, for example, the government last month appointed Katherine Rich, CEO of the Food and Grocery Council, to the new Health Promotion Agency Establishment Board, an entity that replaces the Alcohol Advisory Council of New Zealand, the Health Sponsorship Council and some health promotion activities of the Ministry of Health. Professor Doug Sellman of Alcohol Action New Zealand observed that “Katherine Rich has been one of the most vociferous defenders of the alcohol industry’s desire to continue to pour as much alcohol into New Zealand society as it can. [She] has used her role as an industry spokesperson to attack community groups advocating a stronger Alcohol Reform Bill for the sake of the health of New Zealanders.”

In the United Kingdom, the Conservative government initiated the “Public Health Responsibility Deal for Alcohol,” an industry-public partnership that seeks to “foster a culture of responsible drinking.” These Responsibility Deals develops voluntary industry pledges. According to a recent analysis in the Globe, the newsletter of the Global Alcohol Policy Alliance, “the critics of the pledges say they are not based on evidence of what works, and were largely written by Government and industry officials before the health community was invited to join the proceedings.” As a result, many health and advocacy organizations have refused to participate in the process.

Reducing Taxes

Another way that Big Alcohol companies maintain their profits is by finding ways to pay less tax. According to the global watchdog organization Tackle Tax Havens, SAB Miller, a leading global London-based brewing conglomerate, uses transfer pricing to avoid paying taxes in many countries. SAB Miller has 65 tax haven companies and its tax avoidance strategies are estimated to reduce the company’s global tax bill by as much as 20 percent, giving the company an advantage over local competitors who do pay national taxes and depriving national governments of needed revenue. Tackle Tax Havens estimates that SB Miller’s tax planning strategies have lost the treasuries of developing nations up to 20 million pounds, enough to put a quarter of a million children in school. Its turnover in 2009 was 12 billion pounds and its pretax profits 16 percent.

Another way that Big Alcohol companies maintain their profits is by finding ways to pay less tax. According to the global watchdog organization Tackle Tax Havens, SAB Miller, a leading global London-based brewing conglomerate, uses transfer pricing to avoid paying taxes in many countries. SAB Miller has 65 tax haven companies and its tax avoidance strategies are estimated to reduce the company’s global tax bill by as much as 20 percent, giving the company an advantage over local competitors who do pay national taxes and depriving national governments of needed revenue. Tackle Tax Havens estimates that SB Miller’s tax planning strategies have lost the treasuries of developing nations up to 20 million pounds, enough to put a quarter of a million children in school. Its turnover in 2009 was 12 billion pounds and its pretax profits 16 percent.

In the United Kingdom, the new business-friendly Conservative government reversed a 10 percent increase in the duty on hard cider, again depriving the government of revenues and losing an opportunity to reduce problem drinking. In Scotland, on the other hand, the government has proposed a new minimum price per unit on alcohol, a move intended to discourage volume discounts that serve as loss leaders for alcohol companies but encourage heavy drinking among vulnerable populations.

In sum, Big Alcohol companies are using a variety of strategies to advance their business interests, from targeting new markets and coopting and weakening regulations to opposing new taxes or lowering existing ones. These practices promote the health of their bottom lines but not of the population in the nations where they do business.

Image Credits:

1. MommyJuice

3. ActionAidUK