In a study of how new social networking technologies influence alcohol marketing to youth published in Critical Public Health, Tim McCreaner at the Massey University School of Public Health in Auckland New Zealand and colleagues conclude that social networking systems contribute to pro-alcohol environments and encourage drinking.

Time restrictions on TV advertisements ineffective in reducing youth exposure to alcohol ads

Efforts to reduce underage exposure to alcohol advertising in Europe by implementing time restrictions have not worked, according to new research from the Center on Alcohol Marketing and Youth (CAMY) at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and the Dutch Institute for Alcohol Policy. The report, published in the Journal of Public Affairs, confirms what Dutch researchers had already learned in that country: time restrictions on alcohol advertising actually increase teen exposure, because companies move the advertising to late night.

The takers: State and local governments subsidize corporations

In his campaign for President, Mitt Romney famously charged that 47% of the American population paid no federal income tax and “are dependent upon government, who believe that they are victims, who believe the government has a responsibility to care for them, who believe that they are entitled to health care, to food, to housing, to you-name-it.” A new investigation by the New York Times identifies another category of taker: the corporations who take more than $80 billion in subsidies each year from state and local governments. According to the Times, these governments award $9.1 million in corporate subsidies every hour. More than 5,000 companies have been awarded a total of more than $1 million each in local subsidies. Using the database of state and local government subsidies to corporations created by the New York Times, the table below shows 25 selected companies frequently mentioned in Corporations and Health Watch that received more than $1 million in subsidies. The largest recipient of local government subsidies was the automobile industry. The top three US car companies alone received $4.75 billion in local subsidies in the period reviewed by the New York Times. Most troubling, the Times investigation noted:

A portrait arises of mayors and governors who are desperate to create jobs, outmatched by multinational corporations and short on tools to fact-check what companies tell them. Many of the officials said they feared that companies would move jobs overseas if they did not get subsidies in the United States. Over the years, corporations have increasingly exploited that fear, creating a high-stakes bazaar where they pit local officials against one another to get the most lucrative packages. States compete with other states, cities compete with surrounding suburbs, and even small towns have entered the race with the goal of defeating their neighbors.

The Times further observed that for many communities, “the payouts add up to a substantial chunk of their overall spending… Oklahoma and West Virginia give up amounts equal to about one-third of their budgets, and Maine allocates nearly a fifth.” As national, state and local officials debate about how best to balance revenues and expenses, corporate subsidies deserve further scrutiny. CHW readers can visit the Times searchable database to examine their states’ record or the subsidies received by corporations they are tracking.

|

|

Name of Company |

Total Subsidy |

Number of Grants |

Number of States |

|

General Motors |

$1.77 billion |

208 |

16 |

|

|

Ford |

$1.58 billion |

119 |

8 |

|

|

Chrysler |

$1.4 billion |

14 |

3 |

|

|

Orca Bay Seafood |

$296 million |

4 |

1 |

|

|

Fresh Direct |

$131 million |

9 |

1 |

|

|

Archer Daniels Midland |

$110 million |

23 |

6 |

|

|

Daimler |

$101 million |

24 |

8 |

|

|

Toyota Motor Company |

$96.5 million |

16 |

5 |

|

|

Pfizer |

$92.9 million |

44 |

9 |

|

|

Walmart Stores |

$80.5 million |

176 |

23 |

|

|

Merck and Company |

$60.7 million |

18 |

5 |

|

|

Coca Cola Bottling |

$49 million |

61 |

16 |

|

|

Diageo |

$40 million |

7 |

2 |

|

|

Abbott Laboratories |

$14.7 million |

21 |

9 |

|

|

Pepsi Cola(various franchises) |

$13.3 million |

23 |

9 |

|

|

Jim Beam Brands |

$10.8 million |

7 |

1 |

|

|

Philip Morris USA |

$8.06 million |

5 |

2 |

|

|

Remington Arms Company |

$8.32 million |

13 |

3 |

|

|

Millercoors |

$7.46 |

7 |

4 |

|

|

Smith & Wesson |

$6.16 million |

9 |

1 |

|

|

Lorillard Tobacco Company |

$5.5 million |

2 |

1 |

|

|

Anheuser-Busch |

$4.62 million |

2 |

2 |

|

|

Cargill |

$4.4 million |

9 |

5 |

|

|

Reynolds Tobacco Company |

$3.09 million |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Pernod Ricard |

$1 million |

1 |

1 |

Taxing for health

Taxing products that harm health has long been part of the public health’s armamentarium to reduce the impact of harmful corporate practices. As the global economic crisis continues and the austerity mentality feeds government hunger for new sources of support, politicians look for streams of revenue that can win public support. Recent media coverage of several political debates about taxes designed to promote health illustrate the potential and pitfalls of this strategy.

In France, the new socialist government has proposed a new tax on beer that would increase the price of a half pint of beer by six cents. According to the New York Times, the government offers a public health rationale for the beer tax. There has been an “excessive alcoholization, in particular of youth, with beer more than with wine,” said Jérôme Cahuzac, the budget minister. French beer taxes are among the lowest in the 27-state European Union, he noted, and the scheduled increase would leave them only the 10th highest, lower than in Britain, Spain and the Netherlands.

The Socialist government has also said it will increase the value-added tax, a type of consumption tax, in several sectors of the food industry, including restaurant meals, to 10 percent from 7 percent, partly reversing a reduction made by the previous center-right government. In addition, France’s social security budget, which is in the final stages of the legislative process, also includes heavier taxes on tobacco and new ones on energy drinks. Proposed new taxes total about $30 billion; the increase in the beer tax is expected to generate an additional $625 million.

Not surprisingly, bar owners oppose the new tax, fearing it will cut their business. Others complain that the tax increase is just on beer, not wine, an important sector of the national economy. One supporter of the bill, Even Gérard Bapt, a Socialist legislator, expressed the opinion that the “increase would have to be much more significant to have a real moderating effect on consumption.”

While the socialist government in France is proposing new consumption taxes, Danish lawmakers from the center-right party earlier this month have killed a controversial “fat tax” one year after its implementation, reports the Wall Street Journal. They acted after deciding its negative effect on the economy and the strain it has put on small businesses outweighed the health benefits.

The new tax led to increases of up to 9 percent on products such as butter, oil, sausage, cheese and cream. “What made consumers upset was probably that an extra tax was put on a natural ingredient,” Sinne Smed, a professor at the Institute of Food and Resource Economics in Copenhagen, told the Journal.

The fat tax brought an estimated $216 million in 2012 in new revenue. To make up for the lost revenue, Danish lawmakers will raise income taxes slightly and reduce personal tax deductions. The lawmakers also reversed an earlier decision to create a sugar tax. The fat tax was created in 2011 to address Denmark’s rising obesity rates and relatively low life expectancy. There is little evidence the tax impacted consumers financially, reports the Journal, but it did spark a shift in consumer habits. Many Danes have bought lower-cost alternatives, or in some cases hopped the border to Germany, where prices are roughly 20% lower, or to Sweden.

In a commentary in the New Scientist on the repeal of Denmark’s fat tax Marion Nestle, the New York University nutritionist, disputed the contention that Denmark’s decision was based on health:

Nobody likes taxes, and the fat tax was especially unpopular among Danish consumers, who resented having to pay more for butter, dairy products and meats – foods naturally high in fat. But the real reason for the repeal was to appease business interests. The ministry of taxation’s rationale was that the levy on fatty foods raised the costs of doing business, put Danish jobs at risk and drove customers to buy food in Sweden and Germany…. Governments must decide whether they want to bear the political consequences of putting health before business interests. The Danish government cast a clear vote for business. At some point, governments will need to find ways to make food firms responsible for the health problems their products cause. When they do, we are likely to see immediate improvements in food quality and health. Let’s hope this happens soon.

Another approach to public health taxes has been suggested by outgoing Ohio Congressman Dennis Kucinich. He has proposed a bill HR 4310 End The Childhood Obesity Subsidy Act that would prohibit any company from claiming a tax deduction for the expense of marketing that is directed at children “to promote the consumption of food at fast food restaurants or of food of poor nutritional quality.” In a November press release and video, Kucinich argues:

According to the Institute of Medicine, ‘Aggressive marketing of high-calorie foods to children and adolescents has been identified as one of the major contributors to childhood obesity.’ We can end this tax break, improve our kids’ health and reduce our nation’s debt all at the same time. It’s time to stop subsidizing the childhood obesity epidemic.

Under current law, the federal tax code allows companies to deduct “reasonable and necessary” expenses of marketing and advertising from their income taxes. Fast food marketers get the same break that other businesses do.

So what do these three recent stories from different parts of the world tell us about the use of taxation to promote health and end harmful corporate practices?

First, taxes on products that harm health will always generate intense opposition from a variety of business interests, from local retailers to the world’s largest corporations. Advocates who propose such taxes better expect such opposition and be ready to counter it.

Second, finding the balance between a level of taxation that will actually discourage use and one that is politically feasible in a particular context requires scientific analysis of the available literature and political analysis of the opportunities and constraints. A May 2012 review in the British Medical Journal concluded that

Taxes on unhealthy food and drinks would need to be at least 20% to have a significant effect on diet-related conditions such as obesity and heart disease. Ideally, this should be combined with subsidies on healthy foods such as fruit and vegetables, they add.

Advocates need to assess the potential for achieving health goals with a proposed tax and consider the pros and cons of a variety of alternative strategies before deciding to pursue the tax route.

Finally, as Kucinich’s proposal suggests, changing the tax code to promote health is not limited to taxes that lead to direct increases in consumer prices. Dozens of corporate subsidies enable low prices for unhealthy products and supporting changes in taxation that limit these subsidies may offer promoting political opportunities for discouraging harmful corporate practices. Given the key role that marketing plays in promoting unhealthy behaviors, environments and lifestyles, a closer analysis of tax subsidies for advertising that harms health seems warranted.

The alcohol industry’s plan to give America a giant drinking problem

Why has the United States, so similar to Great Britain in everything from language to pop culture trends, managed to avoid the huge spike of alcohol abuse that has gripped the UK? Tim Heffernan asks in the Washington Monthly. The reasons are many, he writes, but one stands out above all: the market in Great Britain is rigged to foster excessive alcohol consumption in ways it is not in the United States—at least not yet. By deliberately hindering economies of scale and protecting middlemen in the booze business, America’s system of regulation was designed to be willfully inefficient, thereby making the cost of producing, distributing, and retailing alcohol higher than it would otherwise be and checking the political power of the industry.

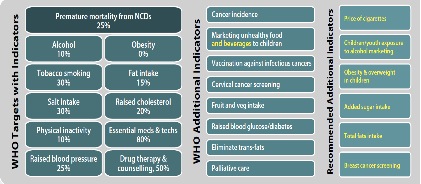

To achieve NCD Targets, WHO should monitor tobacco, alcohol and food industry practices

This week the member states of the World Health Organization are meeting in Geneva to agree on a Global Monitoring Framework for noncommunicable diseases (NCDs). Meeting participants discussed indicators and targets that could be used to assess progress towards achieving the goal of reducing preventable deaths from NCDs by 25 percent by 2025. Also participating in the meeting was the NCD Alliance, a network of more than 2,000 civil society organizations from more than 170 countries. The Global Action Plan and the Global Monitoring Framework on NCDs are a result of the United Nations High-Level Meeting of the General Assembly on NCDs held in New York City in September 2011.

The discussions at the meeting in Geneva focused on what to measure. As shown below, WHO has set 2025 targets as shown in the column on the left and then proposed additional indicators as shown in the middle column. The NCD Alliance has recommended some additional indicators, shown in the column on the right.

These targets and indicators mark an important step forward in controlling NCDs. As Cary Adams, the Chair of the NCD Alliance noted in Geneva , the “commitment to measuring our progress and setting realistic and achievable goals, supported by the investment required, will…make a real difference to those of us who have or will develop NCDs in our lifetime. “

But monitoring changes in health status and health behavior related to NCDs and government NCD prevention policies may not be enough to achieve the stated goals. As several experts have acknowledged, the business and political practices of the alcohol, tobacco and food industries play a critical role in the development of NCDs.[i][ii][iii] Without changes in these practices, it will be difficult to reduce premature deaths. To encourage the discussion of indicators and targets for such monitoring, I suggest some provocative goals for the monitoring of corporate practices.

- Reduce expenditures on marketing alcohol, tobacco and unhealthy foods by the top 10(or 20 or 50) global producers of each of these products by a fixed percentage each year. The alcohol, tobacco and food industries are heavily concentrated with the top firms controlling a significant portion of market share.[iv][v][vi] Since research evidence shows that more marketing leads to more consumption of these products associated with NCDs,[vii] less marketing could reduce exposure to this negative influence.

- Reduce corporate expenditures on lobbying and campaigns contributions for the top 10(or 20 or 50) global producers of alcohol, tobacco and unhealthy food by a fixed percentage each year. Tobacco, alcohol and food corporations have used their political and economic clout to undermine public health protections and to create an environment that allows them to promote behaviors and lifestyles associated with NCDs. [viii][ix][x] Restricting their ability to externalize the costs of the NCDs associated with their products and to thwart the democratic principles of one person one vote could help to prevent premature deaths, reduce government expenditures on health care and restore more democratic processes.

- Require tobacco, alcohol and food companies to commission an independent health impact assessment of any new product or practice and to make the assessment publicly available.

Each year, these companies introduce thousands of new products and practices. Often, however, the adverse health impact is not recognized for years. Requiring companies to hire independent researchers to complete health impact assessments according to uniform standards prior to exposing the population to such practices or products and to make such reports public could discourage companies from releasing into the market inadequately tested products.

How could such targets be monitored? The World Health Organization and other global bodies, the NCD Alliance and its network of NGO partners, national governments and other bodies could each play a role in setting targets and monitoring this indicator. Global organizations could limit participation in international forums to those organizations who achieved targets. Institutional investors could invest in companies that met targets and disinvest from those that did not. National governments could favor companies meeting targets for procurement contracts and penalize those that failed to meet the targets. They could also offer subsidies or tax breaks to companies that achieved targets. Some nations may choose to make these guidelines mandatory, especially for practices implicitly or explicitly designed to increase consumption of unhealthy products by children and young people.

In the current political climate, these proposals will of course elicit intense opposition from corporations and their allies. But 50 years ago the current measures in place to control tobacco use would have been unthinkable. Effective public health officials need to compromise but before they compromise, they have to be able to articulate public health goals that are based on the evidence and have the potential to fulfill the mandate to protect population health. Unless public health professionals, researchers and advocates begin discussing now how to take action to end the corporate practices that contribute to the preventable illnesses and premature mortality that NCDs impose, 50 years from now we’ll still be lamenting the steady increase in the health burden and economic costs imposed by NCDs.

[i] Beaglehole R, Bonita R, Horton R, et al., and the NCD Alliance. Priority actions for the non-communicable disease crisis. Lancet. 2011;377(9775):1438-47.

[ii] Magnusson RS. Rethinking global health challenges: towards a ‘global compact’ for reducing the burden of chronic disease. Public Health. 2009;123(3):265-74.

[iii] Lien G, DeLand K. Translating the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC): can we use tobacco control as a model for other non-communicable disease control? Public Health;125(12):847-53.

[iv] Jernigan DH. The global alcohol industry: an overview. Addiction. 2009 Feb;104 Suppl 1:6-12.

[v] Eriksen M, Mackay J, Ross H. Chapter 18 Tobacco Companies in The Tobacco Atlas 4th Edition pp. 56-57

[vi] Stuckler D, Nestle M. Big food, food systems, and global health. PLoS Med.2012;9(6):e1001242.

[vii] Stuckler D, McKee M, Ebrahim S, Basu S (2012) Manufacturing Epidemics: The Role of Global Producers in Increased Consumption of Unhealthy Commodities Including Processed Foods, Alcohol, and Tobacco. PLoS Med 9(6):e1001235.

[viii] Brownell KD (2012) Thinking Forward: The Quicksand of Appeasing the Food Industry. PLoS Med 9(7):e1001254.

[ix] Freudenberg N. The manufacture of lifestyle: the role of corporations in unhealthy living. J Public Health Policy. 2012 May;33(2):244-56.

[x] Gilmore AB, Savell E, Collin J. Public health, corporations and the new responsibility deal: promoting partnerships with vectors of disease? J PublicHealth (Oxf). 2011;33(1):2-4.

Raising of minimum alcohol prices in Saskatchewan, Canada reduces consumption

A Canadian study on minimum-alcohol pricing published online in the American Journal of Public Health found that a 10% increase in minimum prices significantly reduced consumption for all such beverages combined by 8.43%. There were larger effects for purely off-premise sales (e.g., liquor stores) than for primarily on-premise sales (e.g., bars, restaurants). Consumption of higher strength beer and wine declined the most. A 10% increase in minimum price was associated with a 22.0% decrease in consumption of higher strength beer versus 8.17% for lower strength beers. The neighboring province of Alberta showed no change in per capita alcohol consumption before and after the intervention. The authors concluded that minimum pricing is a promising strategy for reducing the public health burden associated with hazardous alcohol consumption. Pricing to reflect percentage alcohol content of drinks can shift consumption toward lower alcohol content beverage types.

African-American Youth Exposed to More Magazine and Television Alcohol Advertising than Youth in General

By Center on Alcohol Marketing to Youth

African-American youth ages 12-20 are seeing more advertisements for alcohol in magazines and on TV compared with all youth ages 12-20, according to a new report from the Center on Alcohol Marketing and Youth (CAMY) at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. The report is available on CAMY’s website, www.camy.org.

The report analyzes alcohol exposure by type and brand among African-American youth in comparison to all youth. It also assesses exposure of African-American youth to alcohol advertising relative to African-American adults across various media venues using the most recent year(s) of data available.

Alcohol is the most widely used drug among African-American youth, and is associated with violence, motor vehicle crashes and the spread of sexually transmitted diseases. At least 14 studies have found that the more young people are exposed to alcohol advertising and marketing, the more likely they are to drink, or if they are already drinking, to drink more.

“The report’s central finding—that African-American youth are being over-exposed to alcohol advertising—is a result of two key phenomena,” said author David Jernigan, PhD, the director of CAMY. “First, brands are specifically targeting African-American audiences and, secondly, African-American media habits make them more vulnerable to alcohol advertising in general because of higher levels of media consumption. As a result, there should be a commitment from alcohol marketers to cut exposure to this high-risk population.”

The report finds certain brands, channels and formats overexpose African-American youth to alcohol advertisements:

- Magazines: African-American youth saw 32 percent more alcohol advertising than all youth in national magazines during 2008. Five publications with high African-American youth readership generated at least twice as much exposure to African-American youth compared to all youth: Jet (440 percent more), Essence (435 percent more), Ebony (426 percent more), Black Enterprise (421 percent more), and Vibe (328 percent more ). Five brands of alcohol overexposed African-American youth compared to all youth and to African-American adults: Seagram’s Twisted Gin, Seagram’s Extra Dry Gin, Jacques Cardin Cognac, 1800 Silver Tequila, and Hennessey Cognacs.

- Television: African-American youth were exposed to 17 percent more advertising per capita than all youth in 2009, including 20 percent more exposure to distilled spirits advertising. Several networks generated at least twice as much African-American youth exposure to alcohol advertising than all youth: TV One (453 percent more), BET (344 percent more), SoapNet (299 percent more), CNN (130 percent more) and TNT (122 percent more).

- Radio: African-American youth heard 26 percent less advertising in 2009 for alcohol than all youth on stations with the most advanced measurement data available; however, they heard 32 percent more radio advertising for distilled spirits. In these markets, four station formats delivered more alcohol advertising exposure to African-American youth than to African-American adults: Contemporary Hit/Rhythmic (104 percent more), Contemporary Hit/Pop (14 percent more), Urban (13 percent more) and Hot Adult Contemporary (43 percent more).

“Alcohol products and imagery continue to pervade African-American youth culture, despite the well known negative health consequences,” said Denise Herd, PhD, an associate professor with the University of California Berkeley School of Public Health who reviewed the report. “The findings of this report make clear immediate action is needed to protect the health and well-being of young African Americans.”

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey, about one in three African-American high school students in the U.S. are current drinkers, and about 40 percent of those who drink report binge drinking. While alcohol use and binge drinking tend to be less common among African-American adults than among other racial and ethnic groups, African-American adults who binge drink tend to do so more frequently and with higher intensity than non-African Americans.

In 2003, trade groups for beer and distilled spirits committed to placing alcohol ads in media venues only when underage youth comprise 30 percent of the audience or less. Since that time, a number of groups and officials, including the National Research Council, the Institute of Medicine and 24 state attorneys general, have called upon the alcohol industry to strengthen its standard and meet a “proportional” 15 percent placement standard, given that the group most at risk for underage drinking—12 to 20 year-olds—is less than 15 percent of the U.S. population.

Alcohol industry in Australia grooming children to drink by marketing booze-flavored snacks, AMA claims

Australia’s Brisbane Courier Mail reports that a new report by the Australian Medical Association describes how the alcohol industry is using online games that feature alcohol brands, secret parties with online invitations and Facebook to market alcohol to young people. The AMA report says alcohol-sponsored mobile phone apps that provide cocktail recipes, conversation topics or use geolocation technology to recommend nearby bars and clubs are aimed at the young. The industry has also encouraged children to develop a taste for alcohol by marketing Tim Tams flavored with Tia Maria, chocolates flavored with Malibu, vodka flavored lip gloss and fudge and potato chips flavored with Jim Beam whisky, the report says.

Bringing Corporations and Health into the Public Health Curriculum

As public health students and faculty head back to school this week, Corporations and Health Watch continues its tradition of starting the academic year with a commentary on teaching about corporations and health. Our argument for including teaching about the impact of corporations on health in public health and related academic programs is based on the following premises:

- Corporations are the dominant economic and political institution of the 21st century and thus have a profound influence on global well-being.

- The business and political practices of corporations are a modifiable social determinant of health and thus a promising target for public health interventions.

- To achieve local, national and global public health goals of reducing premature mortality, shrinking inequalities in health, and controlling non-communicable diseases and injuries will require making changing corporate behavior as important a public health priority as changing individual behavior.

- Few public health academic programs adequately prepare their students to investigate, analyze or contribute to modifying the corporate policies and practices that harm health.

Photo credit

To be effective in fulfilling their responsibility to prevent illness, promote health and reduce health inequalities, public health professionals should be able to demonstrate the following competencies:

- Identify corporate business and political practices that affect health.

- Develop public health strategies to encourage health-promoting corporate practices and discourage or end health-damaging ones.

- Analyze the public health advantages and disadvantages of various government/market relationships

- Create alliances with consumer, environmental, labor and health organizations and movements that seek to change harmful corporate practices and policies

- Describe the roles of public health professionals and researchers in modifying harmful corporate practices or policies.

These competencies can be developed in several ways. Core public health courses can includes sessions on these topics as they relate to, for example, epidemiology, health policy, environmental health, or health education. Some programs have developed specialized courses on the topic, allowing interested students to pursue this interest. (To see a syllabus for a doctoral course Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Corporations and Health 1900-2012 at City University of New York click here to request a copy.) Or a student-faculty interest group can bring together those who want to pursue research, advocacy or practice on the corporate impact on public health.

Photo credit

For the time being, you’re more likely to find a corporate name on the front of a school of public health than to have corporate practices discussed in the classroom. Fortunately, however, a growing number of resources are available to faculty who want to teach about this topic and students who want to learn more or write papers on corporations and health. I offer here a short list of such sources.

10 Sources on Corporations and Health for Use in Basic Public Health Classes

(with suggestions for use in Epidemiology (EPI), Health Policy & Management (HPM), Social and Behavioral Health (SBH), or Environmental & Occupational Health (EOH) Core Courses)

Biglan A. Corporate Externalities: A Challenge to the Further Success of Prevention Science. Prev Sci. 2011; 12(1): 1–11. (HPM, SBH)

Brandt AM. Inventing conflicts of interest: a history of tobacco industry tactics. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(1):63-71.(EPI, SBH, HPM)

Freudenberg N, Galea S. The impact of corporate practices on health: implications for health policy. J Public Health Policy. 2008;29(1):86-104 (SBH,HPM)

Hastings G. Why corporate power is a public health priority. BMJ. 2012;345:e5124.(EPI, HPM, SBH)

Huff, J. 2007. Industry influence on occupational and environmental public health. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health 13.1: 107–117. (EPI, EOH)

Labonté R, Mohindra KS, Lencucha R. Framing international trade and chronic disease. Global Health. 2011 Jul 4;7(1):21.(EPI, SBH,HPM)

Ludwig DS, Nestle M. Can the food industry play a constructive role in the obesity epidemic? JAMA. 2008 Oct 15;300(15):1808-11.(SBH,HPM)

Stuckler D, McKee M, Ebrahim S, Basu S Manufacturing Epidemics: The Role of Global Producers in Increased Consumption of Unhealthy Commodities Including Processed Foods, Alcohol, and Tobacco. PLoS Med 2012; 9(6): e1001235. (EPI, SBH, HPM)

Wiist, W.H. (Ed). Bottom Line or Public Health. Tactics Corporations Use to Influence Health and Health Policy, and What We Can Do to Counter Them. NY: Oxford University Press, 2010. (relevant chapters for all 4 courses)

Woodcock J, Aldred R. Cars, Corporations, and Commodities: Consequences for the Social Determinants of Health. Emerging Themes in Epidemiology. 2008 Feb 21;5:4. (EPI, EOH, SBH)

In addition to these selected resources, a bibliographic essay on Business and Corporate Practices can be found in the Public Health section of Oxford Online Bibliographies.

Finally, several Corporations and Health Watch contributing writers have websites or blogs that include additional timely material. Check out these sites: David Jernigan, Michele Simon, Bill Wiist.

Previous CHW Posts on Teaching about Corporations and Health

10 Ways to Bring the Health Impact of Business Practices into the Classroom September 2011

Teaching about Corporations and Health June 2010

Teaching about Corporations and Health: Bringing Corporate Practices into Public Health Classrooms December 2007